Last updated January 2025

Why Do We Overshop—and Can We Stop?

Consumers’ Checkbook chatted with author Emily Mester about compulsive buying, hoarding, and other forms of extreme consumerism.

Click below to listen to our Consumerpedia podcast episode.

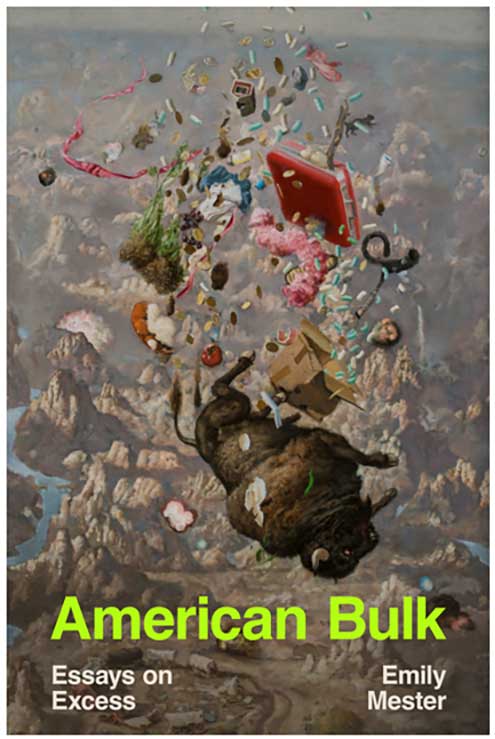

Americans are drowning in stuff. An estimated 20 million of us are compulsive shoppers; 2.6 percent meet the diagnostic criteria for a hoarding disorder. The urge to buy, buy, buy (and keep, keep, keep) fueled Emily Mester’s new book, American Bulk: Essays on Excess.

In the collection of deeply personal stories, Mester explores her own overbuying tendencies, her grandmother’s hoarding disorder, and how we seek satisfaction from shopping for, buying, and rating products we amass.

Checkbook: Your book really taps into America’s rampant consumerism. Did writing it change your own behavior?

Emily Mester: Writing the book hasn’t stopped my own insatiable urge to consume. But it has informed the pathology behind it.

A shopping addiction is kind of clean and cute, so it’s hard to see it as a real problem. It’s not a sort of behavior that you can gently stop. When I’m shopping, it feels like I’m building my future self while lying completely supine. “Oh, I could wear that sweater to a gallery opening!” It lets you warp out of your current moment, like planning a vacation.

I guess we overshop for the same reason people continue other addictive behaviors. It’s an escape mechanism. Whether it’s a Slurpee or shopping, people are looking for dopamine hits.

CB: You are going to try a “no-buy” year in 2025. Have you done one before?

EM: My last no-buy was meant to last for a year and failed after three months. I can’t tell if it failed because I was unrealistically Draconian, or because the task of breaking a shopping addiction is so difficult that such setbacks are expected. Some people have success with budgeted low-buys, while some need to break the habit cold turkey before they can even think about moderation.

There are good arguments for both. Quitting shopping cold turkey, for those three months, was illuminating. I could feel the urge to add-to-cart crawling in my fingers, and it was useful to realize just how chemical the addiction was. That said, it was hard to keep it up. And once I broke, I broke pretty hard because hey—once you fail, why not fail big?

CB: So any tips on doing a no-buy year or month?

EM: Rules are key, but they need to have some flex. You have to try to really understand your habits, where and when and why you cave the most, and let that guide the rules.

I have a rule against eBay, for example, because that site is an endless hole for me. But I’m allowed to buy something at a thrift store in person because I’m actually very methodical and conscientious when I’m holding an item in my hands, and so in-store has never really been my pain point.

I’m keeping a list of all the things I want, and keeping an eye on whether I still want them after a week, a month. Sometimes you look back, and you still want something, and maybe that means it’s worth getting.

But when you look back at an object you once fantasized about, built an imaginary future around, fetishized, and you feel nothing? It’s amazing. It’s like an obsessive crush suddenly dissolving, a spell breaking. I’m constantly chasing that feeling with no-buys. Even if you fail, that experience alone makes them worth trying.

CB: Are consumers becoming savvier about excessive buying?

EM: I think people are becoming more aware of overconsumption, and realizing that it is sort of goaded by these big corporations that try to get us to spend, spend, and spend more.

CB: How do brands feed our shopping addictions?

EM: Advertising and marketing has gotten so clever. I’ve compared ads from the 1960s to what’s happening today, and they’re almost quaint. Older ads kind of said what they meant: “This is a great detergent” or “Your husband will love you if you use this soap.” They were easy to decipher.

Now you have abstract ads and influencer marketing where everyone is selling you something, but under the guise of being your friend.

CB: You write about working at a big-box cosmetics store. What were your takeaways from the experience?

EM: One thing that really surprised me was, for the most part, the customers weren’t monsters. I was warned they’d be bad. [Sometimes] when people are buying, they forget the difference between the stuff they’re buying and the person selling it.

Also, working retail is both physically and psychologically draining. It can feel like you’re caught between the CEO of the store and the customer, and they are both your boss.

CB: One of the essays in American Bulk dives into online reviews. You (hysterically) found yourself nodding along when reading your own rating of a throw pillow, having forgotten you ever wrote it. Any tips on when to pay attention to them?

EM: Reviews are so tricky. The urge to write and read them is understandable. You’re spending money on a product, and you don’t want to be duped. If you’re buying a car or going to a hotel, it makes sense to spend a lot of time researching it.

But if you start treating shopping for a spatula with the same levity, how do you weigh that margin of utility between the time you’re spending and the value of the object? I hunt with the intensity of an apex predator, and then I say, “Wait, that was just a spatula.”

CB: What about leaving online reviews for products or places? In the book, you end up going back and deleting a bunch of ones you previously wrote.

EM: I think leaving product reviews remains a useful service. But leaving reviews of experiences is tough. An experience isn’t a car! [It’s why] I stopped reading reviews of restaurants, because I just don’t know what to believe anymore.

CB: You write about your grandmother’s hoarding disorder in such a sensitive way. Any guidance on dealing with a family member experiencing similar issues?

EM: A phrase I’ve been repeating lately—to myself, to other people—has been “I don’t think you’re bad.” It’s so simple, like a parent soothing a child, but so many of us have outsized, childlike shame for so many parts of ourselves.

In the book, I talk about how I hadn’t seen inside my grandma’s house in years. I became more and more curious about it, seeing it as this wild artifact, like a real-life Hoarders episode. This, understandably, made her even more cagey about letting me in.

When I finally saw the house, it was as extreme as I’d expected. But I was also struck with how human the mess was. A person I loved had made it. Suddenly I could see myself in the mess, could see my dad, could see so many people I know who are dealing with all kinds of things that make it hard to function.

From that point on, I didn’t judge her … I cared more about her emotional health than the pile it had left in its wake.