Last updated November 2024

We looked for 50 products on Amazon; half of what it showed us were paid promos.

Click below to listen to our Consumerpedia podcast episode.

Amazon’s allure has always been convenience. Instead of visiting multiple stores or websites, shop in one place for nearly anything and have it delivered in days.

But the U.S.’s second-largest retailer—and most dominant online merchant—too often steers its customers toward items it gets paid extra to promote. Want an electric toothbrush? When we looked for one on Amazon, 15 of the first 25 items that popped up were “Sponsored” listings.

These ads boost Amazon’s profits, but they create a miserable experience for consumers. Sponsored placements are now so prevalent and poorly labeled that they’re nearly indistinguishable from other listings. And you can’t count on Amazon to display the highest rated or best value products at the top of your search results. Even when we searched Amazon for specific brands, we were still inundated with ads for unrelated lines.

The Federal Trade Commission is suing Amazon, accusing it of monopolistic behavior. Part of that lawsuit alleges that Amazon's e-commerce dominance forces sellers to pay it extra to get noticed at all.

A Sea of Ads

Our researchers assembled a list of 50 products often sold by Amazon and searched the site for each. We completed our test in one day, without logging in, and used Firefox’s private mode to minimize influence from our shopping histories or other data.

The table at the end of this article summarizes our test. On average, about one-half of the first 25 items Amazon displayed (54 percent) were paid placements. For all 50 products we searched for, the top two to five items offered by Amazon were always ads. For a few of our queries, more than 70 percent of the first 25 items Amazon showed were sponsored.

For each product, we did a second search, this time including a brand name (“Clarks men’s dress shoes black” instead of “men’s dress shoes black”). Specificity reduced the number of ads we saw, but not by much. On average, 44 percent of the first 25 items Amazon showed us were still ads; 35 percent weren’t even for the brands we searched for. Often, the brand we wanted didn’t show up until the fifth or sixth spot on the list.

Amazon also sells its own merchandise, usually sold as “Amazon Basics” or “Amazon Essentials.” During our tests, these house brands always came up among the first 10 items. (For the tallies we report on the table below we didn’t count Amazon-brand items as ads; if we had, our counts of ads would be even higher.)

Almost all of Amazon’s search results spotlight one “Overall Pick,” which the company insists merchants cannot pay for. It’s chosen by an algorithm that determines the “best” item according to how often people buy it, how frequently it is returned, and whether it gets favorable customer ratings (four stars or better). That “Overall Pick” should benefit consumers, but our tests showed that, on average, Amazon shoved it down to the eighth spot; in some tests, it landed in the tenth or twelfth spot. When we searched for “Dog food,” Amazon’s overall pick didn’t show up until after 25 other paid-for-placement products.

Particularly irksome: When we searched specifically for Amazon’s overall pick across our 50 products, that item still didn’t show up until after at least four or five ads; sometimes it didn’t appear until after nine or 10 ads.

We redid many of our searches using smartphones and via Amazon’s mobile app. Sponsored items still dominated. Ditto after we logged in; about half of what we saw were still ads.

It’s unclear how much Amazon profits from this setup. For 2023, it reported earning $46.9 billion from advertising. In the second quarter of 2024 alone it reported $12.77 billion from ads, a 20 percent increase over the previous year. But Amazon’s earnings reports lump all its advertising revenue into one category, which includes its retail operations plus Amazon Video and Twitch commercials. Amazon declined our request to provide broken-out earnings from ads displayed in its search listings.

In an emailed response to our requests for feedback on our findings, an Amazon spokesperson said, “Our store is designed to help customers find and discover products we think may best meet their needs, including great brands and products they may not yet know about. Sponsored products are one of the many ways we do this. We are dedicated to providing customers with a world class shopping experience, and we work hard to ensure the search results they see are useful, informative, and help make shopping a little bit easier.”

To its credit, the ads we saw on Amazon were nearly always relevant to our search terms. When we looked for batteries, Amazon didn’t show us socks. And while searching for a specific brand didn’t significantly reduce the number of ads we got, we did see more items from that brand—or at least from a company that competes directly with, say, Duracell.

We also found that Amazon’s filters are your friends: When we punched in a specific brand and used Amazon’s filters to indicate we wanted to see only that brand, most—but not all—of the sponsored items went away.

Is It an Ad? Amazon Often Makes Things Murky

Many of the sponsored listings Amazon showed us—especially at the very top of our search results—included videos or other flashy promos. No wonder: Amazon now operates its own ad agency that clients can hire to boost paid placements.

Of course, all retailers have an incentive to push customers to buy higher profit items. Often, brands pay retailers extra to promote their stuff on end-cap displays or via flashy signs or during sales, and customers typically are unaware of these pay-to-play arrangements.

Amazon’s “Sponsored” listings are labeled as such, but the designation isn’t obvious: it’s marked using tiny gray letters. It also labels items with tags like “Best seller,” “Today’s deals,” “Customers frequently viewed,” “Brands related to your search,” “Inspired by similar searches,” “New arrivals,” or “Trending now.” Like its overall pick designation, Amazon said these labels don’t denote ads; they are driven by its algorithms. But because search results are cluttered with so many labels, it’s difficult to determine what are ads vs. what Amazon just thinks we might like.

Also confusing: Amazon often groups listings in a box bordered by a thin gray line, with a single “Sponsored” label off to the left. (On mobile device searches, these groups are usually within a side-scroll feature.)

The FTC has been battling online retailers for years about their advertising displays. In 2013 it updated its guidance, requiring online sellers to clearly identify ads using prominent borders, shaded boxes, and clear text labels, noting that, “Any method may be used, so long as it is noticeable and understandable to consumers.”

Many listings in Amazon’s search results comply only partially with the FTC’s requirements. Amazon doesn’t highlight ads via different shading and uses very thin borders to separate groups of sponsored listings from others.

Also troubling: Our search results sometimes showed sponsored products before identical, lower-priced items from sellers that don’t pay Amazon extra.

Beware Bizarro Brands

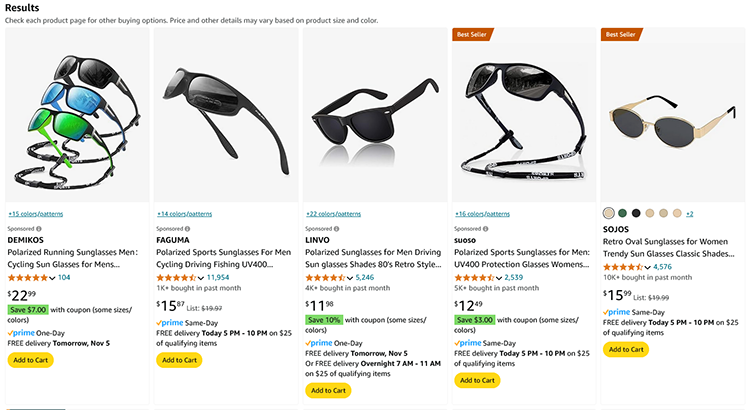

When searching Amazon for our 50 items, we often were served up well-known brands. But products from manufacturers we’d never heard of kept showing up, too. For example, when we asked Amazon to show us “sunglasses,” it showed us the following brands among the first 25 items listed:

- STORYCOAST

- Joopin

- DANAMY

- Dollger

- FEIDUSUN

- ATTCL

- Pro Acme

- swanoble

- WOWSUN

- GQUEEN

- MEETSUN

- Fanshen

- CARFIA

- KALIYADI

- Allarallvr

- Reglaaly

Every single item Amazon showed us in our first page of search results for “sunglasses” was a mystery brand. We saw similar mashups of random letters and words for all the products we looked for, but they were most prevalent for clothing, electronics, and home décor. When we punched in “Ray-Ban sunglasses,” Amazon showed us fewer bizarro-brand options, but they didn’t completely vanish.

These brand names look like typos caused by a cat running across the keyboard, but there’s a lucrative strategy behind them. Before it will sell any item, Amazon requires that a given brand be added to the retailer’s Brand Registry. To do that, companies must first file a registered trademark request with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). And if you want to sell sunglasses on Amazon, it’ll be faster to get a trademark issued for a nonsensical term than for, say, “Ray-Banzes” or even “Shadez,” which might infringe on existing trademarks.

Most of these bizarro brands are from manufacturers in China. Amazon customer reviews suggest many who buy these ghost labels are happy with their DANAMY or CARFIA items, but it’s odd that Amazon treats them the same as it does well-known brands. But maybe it’s not so odd when you consider that Amazon now clearly counts on profits from ads.

FTC Accuses Amazon of Monopolistic Behavior

Shopping on Amazon has always been overwhelming. The company itself offers 12 million-plus unique products plus another 300 million from third-party sellers, which Amazon says account for 60 percent of its sales.

With such a sea of goods, the search tool is critical for customers. According to Amazon’s own data, about 70 percent of its customers stick to the first page of search results, and two-thirds of those who click on products select ones listed there. Amazon also reports that 38 percent of its sales are made within three minutes, and 50 percent happen in 15 minutes or less.

Amazon dominates both U.S. online retail commerce and the way consumers hunt for all products. Several studies estimate that between 60 and 80 percent of consumers check Amazon when shopping for merchandise online. These days, those searches produce large numbers of ads, and not necessarily the best items, the lowest priced ones, or those that ship fastest.

Amazon’s decision to feature more ads might have come from the very top.

“At a key meeting, [Amazon founder and executive chairman Jeff] Bezos directed his executives to ‘accept more defects’ as a way to increase the total number of advertisements shown and drive up Amazon’s advertising profits,” according to an antitrust lawsuit filed by the FTC and 17 states. The FTC’s complaint said that these “defect ads” referred to items that are irrelevant or only somewhat relevant to users’ search terms.

In a summary of its charges, the FTC alleged that “Amazon extracts enormous monopoly rents from everyone within its reach. This includes degrading the customer experience by replacing relevant, organic search results with paid advertisements—and deliberately increasing junk ads that worsen search quality and frustrate both shoppers seeking products and sellers who are promised a return on their advertising purchase.” The FTC also claims that Amazon biases its “search results to preference Amazon’s own products over ones that Amazon knows are of better quality.”

The FTC also alleges that Amazon is charging its sellers exorbitant fees, in many cases close to 50 percent of their revenue: “These fees harm not only sellers but also shoppers, who pay increased prices for thousands of products sold on or off Amazon,” the FTC argued in its filing.

According to the lawsuit, Amazon also uses “anti-discounting measures that punish sellers and deter other online retailers from offering prices lower than Amazon, keeping prices higher for products across the internet. For example, if Amazon discovers that a seller is offering lower-priced goods elsewhere, Amazon can bury discounting sellers so far down in Amazon’s search results that they become effectively invisible.”

Amazon’s statement in response to the lawsuit argued that the case is “wrong on the facts and the law” and said it “look[s] forward to making that case in court.” In a blog post, the company also states that the FTC’s lawsuit would lead to higher prices and slower deliveries for consumers, and hurt third-party businesses.

Other Retailers Pull the Same Stunt

Paid placements within search results are on the rise among Amazon’s online competitors, too. While Google and Facebook have mainly been advertising vehicles for years, now many retailers have shifted from selling stuff to pushing manufacturers and other clients to pay them for placement. Grocery shopping sites and restaurant ordering apps (DoorDash, Uber Eats) are stuffed with sponsored content.

But while we are spotting growing numbers of sponsored listings on the websites for CVS, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Target, Walgreens, and Walmart, those ads haven’t taken over their search results, as they have with Amazon. Unfortunately, this trend will probably continue as these and other companies realize that monetizing their large numbers of users (and the customer data they’ve collected) is incredibly profitable.