Last updated September 2024

Want to Eat Healthier? Read the label!

Matthew Schwartzer is a nutrition label “glancer.” At the grocery store, he spends just a few seconds comparing products, mainly looking at grams of added sugar and protein. “But when it comes to the percentage of vitamins and minerals, I’m not sure how they apply to me. And I never check ingredient lists—there are simply too many confusing terms,” he says.

Like many Americans, the 30-year-old Washington, D.C., consultant isn’t too savvy about the info printed on the back of his canned, frozen, and packaged foods. Only 28 percent of Americans find nutrition labels easy to understand, and more than half don’t regularly check the ingredient list, according to a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) survey.

That may be why some brands are beginning to list a few nutrients on the front of packages. For now, it’s voluntary, but the FDA is considering making it mandatory to provide consumers get at-a-glance info on key facts about what they’re buying and eating.

Here’s how to decode the information on nutrition labels. It’s not difficult to do, and could make a real difference in your health.

Start Here: The Ingredient List

Labels throw a lot at you. Their most important parts are the ingredient list and the nutrition facts panel (the one with all the numbers).

The ingredient list offers a quick read on whether a food or beverage skews more wholesome or ultra-processed. Ultra-processed items are industrially manufactured, with ingredients not used in home kitchens—high fructose corn syrup, dyes, flavorings, artificial sweeteners. Processed stuff (candy, chicken nuggets, instant ramen, etc.) is often high in sodium, unhealthy fats, and added sugar, and low in fiber and whole grains.

These foods are linked to a higher likelihood you’ll develop diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or anxiety and depression. A whopping 60 percent of foods in U.S. grocery stores are ultra-processed, so it’s no surprise they make up 57 percent of the daily calories of American adults and 67 percent for children and teens.

What to look for on the ingredient list:

- Length. Generally, the shorter the better. Ultra-processed foods usually have long ingredient lists.

- The first few ingredients. By law, ingredients must be ordered by weight, with the ingredients accounting for the most weight in a product listed first, followed by the next heaviest and so on. Usually the first and second ingredients are pivotal. For example, you know there’s not much whole grain in that “Honey Wheat Bread” with “enriched white flour” listed as the first ingredient and “whole wheat” appearing five spots later.

- Familiarity: Ingredient lists made up mostly of familiar foods (“milk,” “almonds,” “chicken”) are less likely to be ultra-processed. Terms such as “high fructose corn syrup,” “interesterified oil,” “artificial and natural flavorings,” and preservatives such as “BHA” usually indicate an ultra-processed food.

- Organic. Organic ingredients don’t always make foods healthier or less processed. We counted 27 ingredients—excluding added vitamins and minerals—in Nature’s Promise strawberry organic cereal bar. Many were various forms of organic sweeteners, which your body still registers as sugar!

How to Read the Nutrition Facts Panel

While the ingredient list clues you in to the wholesomeness of a food or beverage, the Nutrition Facts panel drills down its nutritional composition. This is especially useful when comparing similar products. For instance, you can choose a cereal with more fiber and less added sugar, or a frozen pizza that’s lower in sodium.

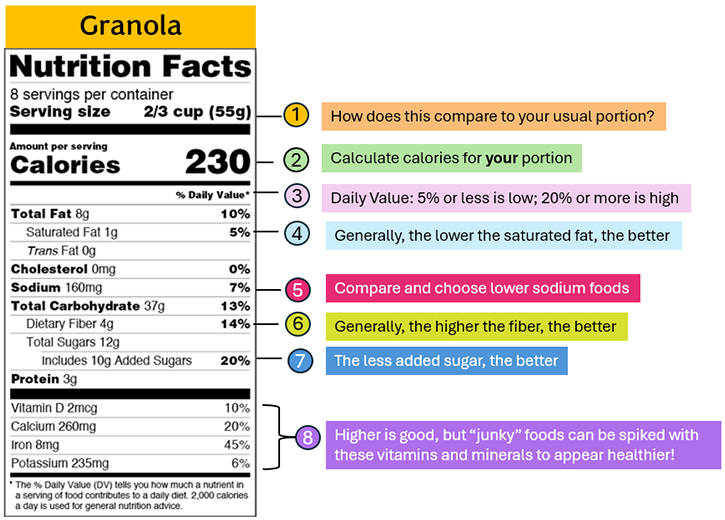

The figure below is our step-by-step guide to navigating the Nutrition Facts panel. While all the nutrients on the label are important, we point to ones people tend to over- or under-do—with health consequences.

1. Serving Size

It’s intended to indicate the typical amount of food people eat per serving.

How to use: Start here, because the rest of the label hinges on the serving size—which may or may not be your typical portion.

Using this granola example of 2/3 cup, here’s how to gauge your own serving. Pour your usual amount of granola into a bowl and measure. If your portion is bigger or smaller, do some quick math to adjust calories and the rest of the nutrients. Same for chips, hummus, and other foods. To accurately compare foods at the supermarket, make sure the serving sizes approximately match up.

2. Calories

It’s the amount in the stated serving size. Don’t be fooled by a seemingly low calorie count—it could pertain to just a quarter or a 16th—or less—of the entire package!

How to use: After you determine your typical serving, calculate the calories.

3. Percent Daily Value

This is the approximate percentage of nutrients (such as dietary fiber and calcium) you need daily. Consider these percentages “close enough,” since, when it comes to nutrients, one size does not fit all. The macronutrients (total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, total carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and total and added sugars) are based on the needs of someone taking in 2,000 calories per day. You may need more or fewer calories.

It’s the same with micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). For example, there are nine different recommendations for milligrams (mg) of iron, based on sex, age, or if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding. The nutrition label wouldn’t even fit on a package if each group were represented. So the FDA created one set of numbers covering most of the population and called it the “daily value.”

How to use: Consider a food “low” in a nutrient if it contains just five percent or less; 20 percent or more is considered high. Low is good when it comes to nutrients like sodium, and high is good for nutrients like fiber.

4. Saturated Fat

Saturated fat, in excess, raises LDL, or “bad cholesterol.” In turn, too much LDL can narrow and clog arteries, causing heart disease and stroke. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the government’s nutrition guidelines, recommend limiting saturated fat to no more than 10 percent of total calories.

(Trans fat is even riskier than saturated fat, but now that the main source—partially hydrogenated oil—has been banned from the food supply, it’s no longer an issue.)

How to use: To limit saturated fat, purchase more foods containing closer to five percent and fewer foods that have 20 percent or greater. Foods high in saturated fat include dairy (except fat-free), fatty meats, poultry with skin, and packaged foods made with butter and “tropical oils”—coconut, palm, and palm kernel oils.

5. Sodium

Sodium is a mineral we need for muscle and nerve function, to regulate fluids in the body, and for other important tasks. In excess, it raises blood pressure; high blood pressure can lead to heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease. The government’s Dietary Guidelines consider 2,300 mg of sodium per day the maximum safe amount (but check with your doctor; some people should consume even less).

How to use: Compare labels, choosing lower sodium versions of similar foods. Breads, chips, pickles, pizza, and soup are usually high in sodium, but because sodium makes its way into so many foods, check all labels.

6. Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber is a carbohydrate found in plant foods. Although we don’t have enzymes to break it down, our gut microbiome (the trillions of bacteria residing in the intestinal tract) do. Higher-fiber diets are linked with a more diverse microbiome which may reduce risk of type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases. And fiber works in other ways to combat constipation and heart disease.

How to use: Choose higher fiber foods, but not at the expense of an otherwise “meh” ingredient list. For example, you’re better off with a 100 percent whole grain bread with two or three grams (g) of fiber per slice than a higher fiber bread made with refined flour plus bran. That’s because benefits of whole grains go beyond fiber to encompass vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients (beneficial substances found in plant foods).

7. Added Sugars

Added sugars include white sugar, honey, high fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrate, and any other calorie-containing sweetener. Along with obvious sources—soda, candy, cookies, and other treats—sugar lurks in breads, salad dressings, fruit yogurt, and many sauces. Diets high in added sugars are linked to weight gain, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.

“Added Sugars” do not include artificial sweeteners or naturally occurring sugar, such as lactose (milk sugar) or the sugar in fruit (such as in the raisins in raisin bran cereal). But the “Total Sugars” line on the label encompasses both naturally occurring and added sugars (but does not include artificial sweeteners).

How to use: Opt for foods with less added sugar. The government’s Dietary Guidelines recommend that we cap it at no more than 10 percent of total calories. That works out to 50 g for the 2,000-calorie daily standard. Depending on your calorie level, your limit may be higher or lower.

8. The Rest of the Vitamins and Minerals

Most U.S. food brands must list vitamin D, calcium, iron, and potassium since Americans tend to be low in these nutrients. But labels can include more than these four. Be aware that manufacturers inject vitamins and minerals into otherwise not-so-healthy products. For instance, muesli—an oat, fruit, and nut cereal with no added sugar or nutrients and just two percent of the daily value of calcium—is a more wholesome choice than an ultra-processed breakfast bar spiked with vitamins and minerals boasting 10 percent of the daily value of calcium.