Last updated November 2018

We hit the panic button—290 times!—to test the value of these gadgets.

Note: After we released the following report GreatCall was rebranded as Lively Mobile. As of May 2022, Lively Mobile and Best Buy (its parent company) reported that customers who want devices that can connect to 911 directly could still do so by purchasing Lively Mobile Plus devices.

Life Alert’s “Help, I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!” ads from the 1980s introduced millions of late-night TV viewers to medical alert devices—and probably was the first viral meme. If grandma couldn’t reach a phone to dial 911, she could press a button on the company’s device, which connected her to a Life Alert operator.

Of course, technology has changed a lot since those years when landline phones were the norm, cell phones were for the rich and famous, and only half the U.S. population was served by 911 centers. Today more than 3 million (mostly senior) customers own these gadgets, and many models can use cell signals to communicate. They cost about $11 to $52 a month.

How to find the best one? We’ll get to that. More important is to ask if a medical alert device is the best tool for the job of calling 911 for help. Most of them are not, and our tests of several different models found many companies actually delay emergency response, not facilitate it.

Send Help!

Why You Might Buy

These devices do supply a panic button right at hand—on a wrist or neck pendant, or on the bedside table as it recharges overnight. If you’re worried that you might get injured or in a situation where you can’t reach a phone to dial 911, they can provide that support—although with most devices getting help will take more time than calling 911 directly (see below). And many devices can be equipped with optional fall-detection features that automatically call their monitoring companies if you take a tumble (or the device falsely senses a fall, which happened often with the units we tested). But a pretty narrow group of seniors has these needs.

On the other hand, medical alert devices are more helpful to callers who have a less-than-911 problem. “Nine times out of 10, when people press our button, they don’t necessarily need 911. They want us to call someone else,” such as a friend or relative, says Bob Kelley, president of ResponseNow. So for $130 to $625 for the first year (price of device and monthly monitoring fees), you can get a device that works kind of like a cell phone but is far easier to operate—after all, there’s usually just one button to deal with.

On the other hand, medical alert devices are more helpful to callers who have a less-than-911 problem. “Nine times out of 10, when people press our button, they don’t necessarily need 911. They want us to call someone else,” such as a friend or relative, says Bob Kelley, president of ResponseNow. So for $130 to $625 for the first year (price of device and monthly monitoring fees), you can get a device that works kind of like a cell phone but is far easier to operate—after all, there’s usually just one button to deal with.

If you want one of these devices, GreatCall is a standout among the models we tested. It’s easy to use, reliable, quickly connects to its call center or directly to 911 (which the other devices can’t do), and offers reasonable pricing. (See below for more test results.)

Detour

Many Devices Delay EMS Response

With help from the Arlington County, Va., Emergency Communications Center, our researchers tested 11 models and found disturbing deficiencies with most of them, especially during the worst-case scenario requiring 911 help. Some performed so terribly that we’re afraid their customers’ safety is at risk.

In an emergency, most of these devices get in between you and the help you need.

Among the 11 units we tested, only GreatCall’s can directly connect you to 911. With the rest, pressing their alert buttons first connects you to a company call center, and people there must then determine whether to contact your local 911 dispatchers or police, fire, or Emergency Medical Services (EMS) directly for you. Those tasks—waiting for the call center to pick up, talking to you through the device to assess your need, calling 911 for you, relaying your information to a 911 operator—consume precious time.

What’s the need for speed? “Response time is absolutely critical for effective emergency response, and it’s more critical the more serious the emergency,” says Christopher Carver, director of Public Safety Answering Point/9-1-1 Operations for the National Emergency Number Association (NENA).

At peak traffic, 911 centers aim to answer 90 percent of calls within 10 seconds and 95 percent within 20 seconds. Dispatchers are intensely trained to quickly interrogate the caller to assess the situation, determine the victim’s location, and decide who to send to help. They also can begin instructing callers to give CPR or stem bleeding before medics arrive.

At peak traffic, 911 centers aim to answer 90 percent of calls within 10 seconds and 95 percent within 20 seconds. Dispatchers are intensely trained to quickly interrogate the caller to assess the situation, determine the victim’s location, and decide who to send to help. They also can begin instructing callers to give CPR or stem bleeding before medics arrive.

EMS personnel like to get on-scene within four to five minutes of dispatch in urban areas, says Brent Myers, president of the National Association of EMS Physicians. Studies show that “any addition to the time of response has a negative impact on the outcome,” says Carver.

Thus 911 operators, who have worked to improve and perfect their national system over the last 50 years, are the top guns of emergency dispatch.

Nevertheless, most alert devices we studied delay your ambulance by inserting typically lesser-trained agents between you and the pros. “Any interaction outside the scope of the 911 center has the potential to increase the amount of time between the discovery of an incident and the dispatch of emergency response resources, assuming all other things are equal,” says Carver.

The manufacturer of one of the devices we tested agrees.

GreatCall says its 5Star call centers are “not a substitute for 911. GreatCall recommends that all 5Star subscribers who experience a potential emergency always bypass 5Star and contact 911 directly” by phone or via the GreatCall device, which is the only one we tested that offers a direct-to-911 call option.

Another problem with using medical alert devices is that, when their call centers finally get around to ringing up your police, fire, or EMS, their calls might get treated as non-emergency requests. That could cause more delays. When we tested devices while sitting in Arlington’s 911 center, we saw its system put on hold for several minutes calls coming from our medical device monitoring centers because those companies dialed a 10-digit non-emergency number for Arlington Fire and Rescue, rather than 9-1-1. Arlington’s system is understandably set up to automatically prioritize 9-1-1 calls over others.

In our tests, many of the medical alert device call centers were too slow to answer.

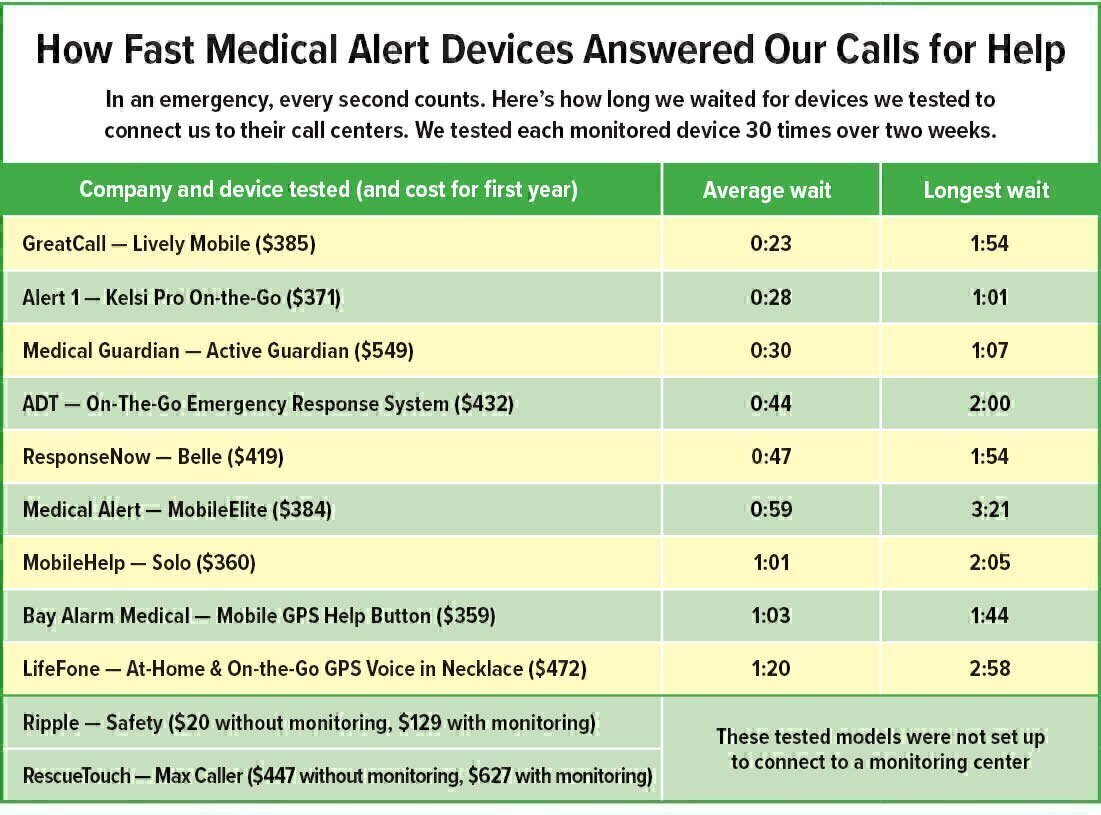

We tested the response times from call centers of devices, plus asked about their protocols and location-finding capabilities in a variety of spots: Arlington 911 headquarters, a suburban fire station, and six other urban and suburban locations. We conducted 30 tests for each of nine devices that we set up with call monitoring, plus 10 tests each for two devices that were set up to notify only friends and family—a total of 290 trials.

The table below reports the results of our tests. As you can see, three of the devices we tested on average connected us to their call centers in 30 seconds or less. But some performed far more poorly: Three other devices made us wait more than one minute, on average. And with some units the wait sometimes was more than two minutes; in one instance we had to wait more than three minutes. An extra one-minute wait during a medical emergency is a long time; a three-minute wait is an eternity.

While Arlington County assisted Checkbook as a neutral testing site, it does not endorse any products or companies.

During our tests, after we hit their panic buttons devices typically beeped, blinked lights, or otherwise indicated that there was a “call in progress.” But when we pressed the button on the Medical Alert MobileElite in one test…silence: no beeps, no blinks, nothing. Was it working? Finally, after a full minute and 12 seconds, a computer voice came to life: “Dialing the emergency response center now.” Dialing only now?! More seconds passed before a human answered—a minute-and-a-half into the call. That’s a long way from 911’s 10- to 20-second standard—and even then it was only a Medical Alert operator who answered, not a 911 dispatcher.

Keep in mind that because we measured only how long it took medical alert companies to answer our calls, our test-results times don’t include the additional delays you’d experience waiting for a company to call your local police, fire department, or EMS—and then perhaps wait even longer for the 911 center to answer its non-emergency call.

Vijay Karia, chief digital officer of Connect America, which makes Medical Alert products, told us his monitoring and support agents answer calls in only 12 seconds, on average. In our 30 tests, we clocked them considerably slower, at an average of 59 seconds.

The three best performers were reasonably on-par with 911, answering within 30 seconds or less, on average. But remember that their operators are not the real 911 either; they’re intermediaries. And all of the devices—best-to-worst—made us wait at least once for more than one minute just to have our call answered.

Devices are prone to false alarms.

These gadgets can also pose a risk to public safety, according to emergency response experts we interviewed. One 911 manager flatly labeled them “a [very bad word] menace.” Among the 911 community, medical alert devices are notorious for false alarms and for providing inadequate location information, both of which needlessly tie up 911 staff and sending EMS crews on wild goose chases, delaying responses to real emergencies.

Some of the devices we tested sent false alarms during shipment to us. Once they arrived, even more false alarms. On a few occasions our receptionist looked up to find paramedics at our office front door, ready with gurney, oxygen, defibrillator, the works.

Some of the devices we tested sent false alarms during shipment to us. Once they arrived, even more false alarms. On a few occasions our receptionist looked up to find paramedics at our office front door, ready with gurney, oxygen, defibrillator, the works.

We say optional fall-detection features should be avoided unless you are buying for someone who is confined to bed. Our devices were also set off by bumpy car rides, moving them from table to desk, or just…sitting still. At other times we couldn’t trigger fall detection alerts by deliberately dropping the things.

Where’s Uncle Waldo?

Location Is Another Problem

In our tests, medical alert companies often had trouble determining where our calls were coming from—exactly or even within a reasonable margin of error. That jibes with what we were told by 911 managers, who complain they often “…were not able to get a good location, or the location was from an hour before, or there was no phone number, so we couldn’t call them back,” says Angelina Candelas-Reese, 911 systems manager for Arlington County, Va.

In one such incident, a Medical Guardian device called Arlington 911 at 11:18 a.m., but five minutes later responders reported they were still “unsure of exact location,” according to an incident report obtained by Checkbook through a Freedom of Information Act request. Four more minutes after that, the report says, “No answer at the number provided” by Medical Guardian.

Twelve minutes later, the report says, “Company has no subject description, no date of birth, no further information,” at which point the incident was closed without action—21½ minutes after the call came in.

“Location information is the most critical piece, because if we can’t find you, we can’t help you,” says Martha Carter, 911 administrator for Caddo Parish 911, which covers Shreveport, La.

And if the information is imprecise, time can be wasted hunting for the caller. All of this becomes a problem if the caller is lost, doesn’t know where he or she is, or can’t verbally communicate a location, as might be the case with a stroke.

To simulate that worst-case scenario, we engaged the panic button of our Medical Alert MobileElite device. When its call center answered, our researchers remained silent. After two minutes of asking if we were okay, the agent said she’d try to call us back. Twenty seconds later, she called the device. We remained unresponsive. At the three-minute mark, the agent called our emergency contact, at which point another Checkbook tester, posing as the caller’s relative, let the operator off the hook by saying the “victim” just came home and was okay.

But where was the device located? Medical Alert had no clue.

When testing devices, our researchers asked each company to supply any info it had on our present location. Some were usually able to accurately determine our device location spot-on or reasonably close, while others put us blocks away, and one time Bay Alarm Medical’s call center “found” us halfway across the globe, in Asia. In general, these devices have trouble locating callers from high-rise buildings in urban areas: To which of 10 or more floors should EMS go?

Some of the devices we tested use the latest, best location technology, but we didn’t notice clearly better location accuracy in those models vs. the others. Ripple’s location info, however, was more accurate compared to any of the devices we tested. Ripple was the only device we tested that required being linked to a cell phone, and it uses satellite GPS coordinates drawn from that phone to locate the caller with the same precision of Apple’s and Google’s mapping apps.

But in fairness to medical alert device manufacturers, smartphones don’t always provide great location information to 911 either. But that’s changing. This year, AT&T, Apple, Google, T-Mobile, Sprint, and Verizon began flipping the switches on new technologies that transmit highly accurate digital location information to 911 centers—if they have upgraded their software to receive it. The new technology gives 911 dispatchers the same detailed location data already collected by most smartphones from satellites, cell towers, Wi-Fi, and other sources for use with mapping apps, Uber, and other software. These changes promise to dramatically improve emergency response times.

Still Buying?

Here Are Our Recommendations

Because most medical alert devices delay response from emergency personnel, and many provide less-than-precise location data, we can’t recommend most of those we tested.

But one stood out: the GreatCall Lively Mobile. Our reasons are detailed in below. Consumers who want a medical alert device should also consider the GreatCall Lively Wearable paired with the 5Star Urgent Response smartphone app. (We tested the responsiveness of 5Star service using the Lively Mobile device. The Lively Wearable is not an alert device by itself; it links to the same 5Star service via Bluetooth to the app available for most smartphones, which we put on a GreatCall Jitterbug prepaid phone.) We think only seniors with specific needs (disabilities, living alone) should bother buying it, but for them GreatCall covers a lot of bases at a fair price:

- Pushbutton direct to 911. Our preference for GreatCall starts with the fact that unlike the other devices it offers the option of calling 911 direct, which eliminates the delay of having to first talk to a monitoring company. Note: After we released the following report GreatCall was rebranded as Lively Mobile. As of May 2022, Lively Mobile and Best Buy (its parent company) reported that customers who want devices that can connect to 911 directly could still do so by purchasing Lively Mobile Plus devices.

- Fast. In our tests, GreatCall picked up faster than the others.

- In close reach. Lets you keep its panic button on your wrist or on a lanyard hanging from your neck.

- Latest location data. Because the software in the Wearable plus 5Star app combination can collect location data from a paired cell phone, it can hand off to 911 the latest-technology info. GreatCall’s software is compatible with iPhone 8 or Android 4.4 or later models.

- Friends and family help. For less-than-911 situations, GreatCall gives you the option of calling its call center, which can then connect you to friends or relatives.

- High-level call-center training. GreatCall’s dispatchers have Emergency Medical Dispatcher training and certification from the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch, which is on a par with what 911 dispatchers get.

- Mid-priced. Total cost for the Lively Mobile is about $50 for the device, a $35 activation fee, then $25 per month for the basic service. The Wearable plus 5Star app is cheaper still, at $230 for the first year. But you must also pay extra for a cell phone (and monthly cell service costs) for the Wearable to contact the 5Star monitoring service.

Another good but more expensive wearable device option is to buy a smartwatch for a few hundred dollars. Connecting it to a smartphone means you’ll have pushbutton access to real 911 right on your wrist. You may have to upgrade to a later-model phone. For example, the new waterproof Apple Watch Series 4 ($499) requires an iPhone 6 or later model. If you don’t already have one, a 32GB iPhone 6S costs about $350 new or $230 used.

More to consider when shopping for any device:

- Avoid contracts. The services we tested don’t require long-term contracts. We didn’t include Life Alert, the classic “Help, I’ve fallen!” company, in our testing because it requires a three-year contract.

- Take a trial. Deal only with companies that offer a free trial period of at least 30 days. Three devices we tested didn’t offer free trials, requiring you to pay for a month or two to try them out: ADT, Medical Guardian, and Ripple.

- Test it. See how quickly the call center answers when you’re at home and from spots you frequent. Hit the button a dozen or more times, spreading out your tests over different times and days—and ask call center operators where they peg you. If the device can’t find you reasonably well or they consistently take more than 30 seconds to answer calls, return it.

- Just say no to fall detection. Unless you’re buying for someone who is confined to a bed, we don’t recommend this feature. In our tests, it created many false alarms.

- Fill out your profile. As soon as you get your device, complete your customer profile with as much detail as possible about medical conditions and the drugs you’re taking, including dosage and times per day. The more the call center operator knows about you, the better they and emergency responders can help.