Last updated November 2019

Manufacturers, mega retailers, and Google often hide the lowest prices for big-ticket items. Here’s what they do—and how you might still find deals.

We often hear that consumers enjoy low prices due to fierce competition among Amazon, Walmart, Target, and other mega-retailers—plus easy-to-compare prices using Google and other search engines. But for big-ticket items like appliances, TVs, computers, bikes, and more, our researchers discovered that’s often not the case: It’s hard to find bargains anymore.

We collected and compared prices for 200-plus big-ticket products at mega-retailers and websites. We found that confining our shopping efforts to Amazon, Best Buy, Google, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Target, and Walmart often turned up only small price differences. That’s because sellers, in collaboration with manufacturers, work hard to limit price competition. It’s one reason the U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission, and 50 state attorneys general are now investigating Amazon, Google, and other tech giants.

To test several deal-finding strategies, we had one of our undercover shoppers scour the marketplace for the best prices on 30 big-ticket items using 44 different retailers, online shopping tools, and strategies. She found that good deals often still do exist—but finding them can be a chore. This article shares how we uncovered the best prices for specific buys. Click here for additional tips and strategies for saving when shopping online. But first, let’s look at how manufacturers, retailers, and internet overlords try to prevent you from easily finding bargains.

To test several deal-finding strategies, we had one of our undercover shoppers scour the marketplace for the best prices on 30 big-ticket items using 44 different retailers, online shopping tools, and strategies. She found that good deals often still do exist—but finding them can be a chore. This article shares how we uncovered the best prices for specific buys. Click here for additional tips and strategies for saving when shopping online. But first, let’s look at how manufacturers, retailers, and internet overlords try to prevent you from easily finding bargains.

Killing Price Competition

The internet delivers so many sellers and ways to buy that it seems awash with companies clamoring to offer the best deals. By making it easy to compare prices at multiple retailers, Amazon, Google, and other search engines make it look like they’ve scoured the web for low prices. All that competition should mean lots of low-cost buying options. But search engines, manufacturers, and big-time sellers actually use a few tricks to maintain their dominant market shares and prevent you from easily seeing better deals offered by their smaller competitors.

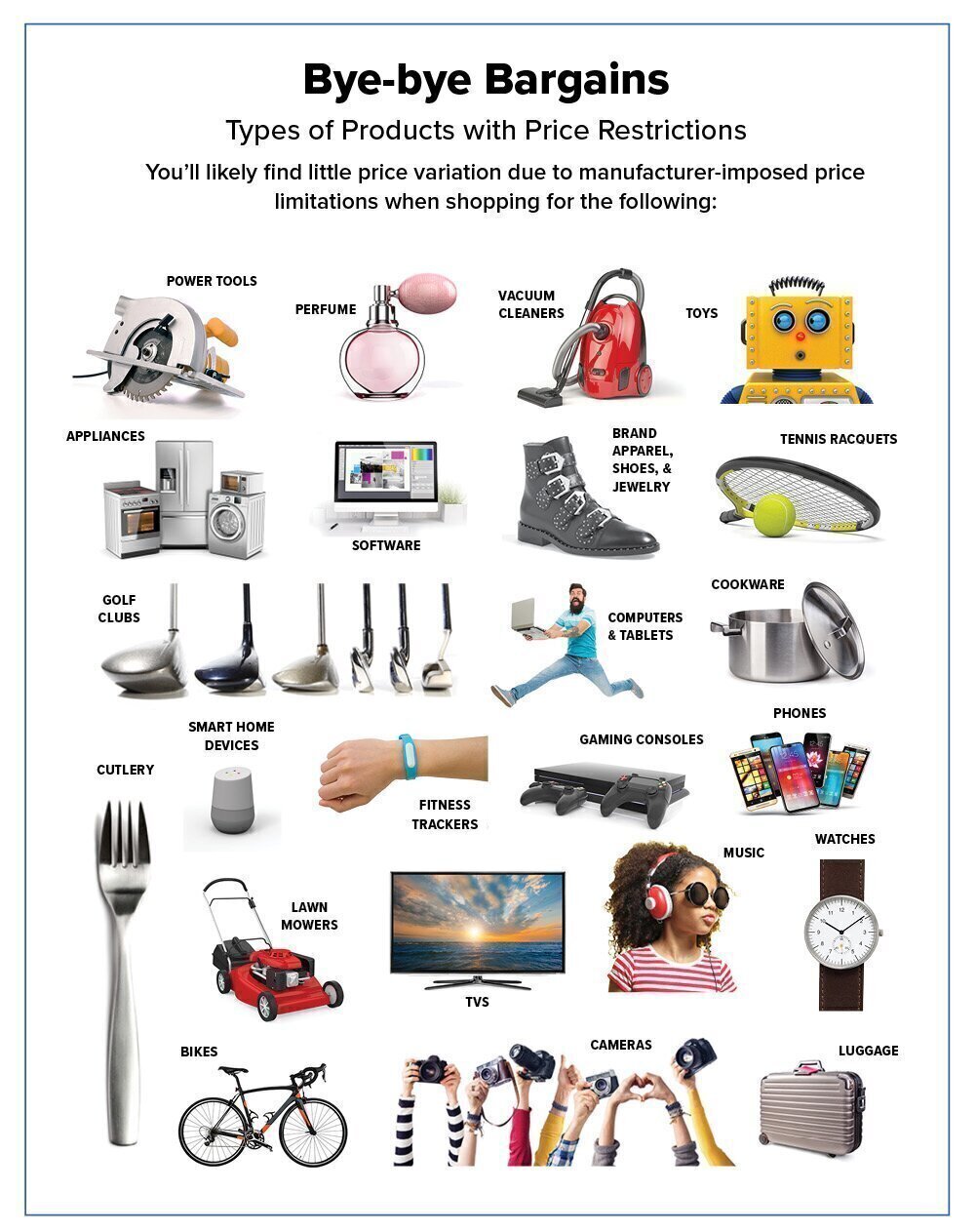

Manufacturers Set Minimum Advertised Prices

For some products, no matter how much you shop you’ll find the exact same prices everywhere. That’s because their manufacturers strictly control pricing and don’t allow any discounting or price competition among outlets selling their stuff. You likely won’t see any differences in prices offered for the latest models of Apple iPhones; Sony PlayStation, Xbox, and Nintendo gaming systems; bikes; and some other products.

A more common—and more subtle—way manufacturers and big retailers reduce retail price competition is with “minimum advertised price” policies—MAP for short—which prohibit retailers from advertising products for prices below preset minimums. If a product’s MAP is $499, that’s the lowest price retailers are allowed to advertise, including on their websites. Retailers are free to sell the item for less than $499, but because they can’t list a lower price publicly, you can’t easily find that bargain.

Manufacturers keep track of which wholesalers and retailers buy their products, and use web-crawling software to monitor what prices those companies advertise online. If a retailer lists a lower-than-MAP price, it may get its supply cut off.

Sellers can’t even sneak around MAP by, say, offering a storewide percent- or dollars-off discount for all of the products they sell. For example, look closely at a Bed Bath & Beyond “20 percent off” mailer and you’ll see that the fine print excludes dozens of brands due to MAP restrictions.

You might think, “Hey! This seems like illegal price-fixing! What gives?” Well, it used to be illegal—from the early 1900s, when most federal antitrust laws were enacted, until 2007, when “the U.S. Supreme Court changed its mind,” says Herbert Hovenkamp, professor of legal studies and business ethics at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. (MAP, however, may still violate some state laws, if enforced.)

It’s still illegal for manufacturers who are supposed to compete against one another to collaborate on pricing (for example, LG and Samsung can’t work together to decide what to charge for TVs), and retailers are still barred from joining forces (Home Depot and Lowe’s can’t agree to charge the same prices for stuff).

But manufacturers are allowed to discuss pricing with their retailers—and impose restrictions like MAP on them—so long as they do so unilaterally. But as Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer noted in his dissent of the high court’s 2007 decision, these practices “can diminish or eliminate price competition among dealers.” We agree and think MAP policies are contrary to the definition of a free and fair market.

Manufacturers argue that MAP and other pricing requirements eliminate price wars, which could lead to poor service from sellers getting by on thin profit margins. And many brands want to keep local stores open and showcasing their products; eliminating price constraints might put the remaining brick-and-mortars out of business since they’d have to compete with online-only retailers and their lower overhead costs.

Another theory: “If dealers can’t compete on price, they have to compete on better-quality service,” says Hovenkamp.

For example, until 1978 U.S. airlines had to charge the same coach-fare prices for the same routes. Since they couldn’t compete on price, airlines had to compete for flyers by offering better service than their rivals.

But we think the marketplace should provide consumers with honest advertising and price information. By hiding lower prices and reducing or eliminating price competition, agreements like MAP keep prices artificially high and make it difficult for consumers to save money by shopping around. Since MAP removes the need to compete on price, this also favors dominant large retailers, which no longer have to worry about price competition from new or smaller retailers that might offer lower prices to drum up business. We also think there’s far too little disclosure from manufacturers and retailers about how they determine prices.

And we don’t believe that MAP helps create and maintain high service-quality levels. If minimum pricing guidelines for, say, appliances allow sellers to focus on service, then why are the ratings we get for the largest appliance retailers—Best Buy, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Sears—so dreadful? We see little evidence that eliminating price wars has led to better customer service from these chains.

It’s impossible to know how much these practices hurt consumers. But we think they are costing them a lot, especially those who bother to shop for low prices.

In the 1990s, before most manufacturers adopted pricing rules, Checkbook published a guide to the best prices we could obtain from stores for thousands of big-ticket items—for appliances, bikes, TVs, and more. Twice a year our staff asked all stores to quote prices they would honor for our subscribers for items they sold; we compared the bids stores sent us to prices we found via undercover shopping and reviews of ads, then published the stores’ lowest price commitments that we considered true bargains. We saw big store-to-store price differences when we could ask stores to compete for our members’ business. But MAP largely eliminated that type of competition.

Our researchers still make tens of thousands of price checks each year, for everything from groceries to hardware to cabinets to hearing aids. We regularly find that some stores charge more than double what their nearby competitors do for the exact same items. Even for groceries, which are sold with very tight profit margins, the least expensive chains offer prices more than 30 percent lower than the most expensive ones. But for big-ticket items governed by minimum pricing guidelines, we find only small price fluctuations from seller to seller.

Google This: “Search Engine Bias”

Despite manufacturer policing of MAP, some companies still break the rules and advertise lower-than-allowed prices. But because of something called “search engine bias,” you still might not find them so easily.

Google became wildly popular by promising cold-blooded, algorithm-driven search results in a simple format unencumbered by advertising or other financial conflicts. Now…well, not so much.

Google became wildly popular by promising cold-blooded, algorithm-driven search results in a simple format unencumbered by advertising or other financial conflicts. Now…well, not so much.

While Google’s algorithms still consider relevance, site traffic, and other factors to determine which sites show up where in its search results, these days Google gives heavy preference to businesses that pay it a lot of money for the privilege of appearing in the prime real estate of the search-engine giant’s pages.

If you look for “best price for [the thing you’re buying],” you’d think Google’s search results would list the best deals first. But that’s not so. Google and other search engines award preferential top-of-results spots to retailers that pay them, not necessarily to the actual best bargains you asked them to search for.

For example, when our shopper searched for the lowest price for an LG 75-inch 4K Ultra HD LED TV, model 75SM8670AUA, the best price Google showed us on its first page of results was $2,063. But we easily found better deals elsewhere: We’d save more than $290 off Google’s best price by buying that TV from Costco, and other non-membership stores offered it for $260 to $360 less than Google.

By steering its massive number of searchers toward the businesses paying it commissions, we think Google creates an unfair marketplace. Sellers who don’t pay Google likely won’t get a chance to compete for customers there. Google’s agreements with large companies that can afford to pay it hefty commissions, or spend the most on advertising there, mean smaller companies and startups get shut out, even if they want to offer the lowest prices.

The attorneys general of all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia suspect the same thing. In September, they announced an investigation into whether Google illegally uses its dominance to thwart competition.

“It’s about time the federal government is starting to look under the hood, and we really appreciate the involvement of the state attorneys general, who are sometimes less risk-averse in pursuing investigations,” says Susan Grant, director of consumer protection and privacy at the Consumer Federation of America.

“The same concerns that have arisen in Europe, about the potential for Google to abuse its outsize market power to do things like manipulate search results, have been expressed here in the U.S.,” says Grant.

In 2017 the European Commission (E.C.) fined Google $2.7 billion for abusing its dominance as a search engine—on top of two other fines over the previous two years for anticompetitive behavior, for a total of $9 billion.

The 2017 E.C. action came about because the search giant gave “illegal advantage” to its own “Google Shopping” service—a better position at the top or right-side position on the first screen of search results. Consumers are more likely to click links in those locations. At the same time, Google’s algorithm intentionally demoted competing comparison-shopping service results, the E.C. said. Google is appealing the action, but has made changes in Europe that the E.C. described as “positive.”

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission also has investigated Google for this type of bias. But in 2013 the FTC closed the case without taking action after the FTC concluded that the practices “could be plausibly justified as innovations that improved Google’s product and the experience of its users.”

In July, however, the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division opened a review to determine if leading online search platforms like Google are “engaging in practices that have reduced competition, stifled innovation, or otherwise harmed consumers.”

Amazon Price Optimization

Like a good capitalist, Amazon seeks to sell all its merchandise at the highest possible prices. Amazon’s size and data-analysis resources give it a big advantage over consumers: It can track their search and purchasing behavior, and crawls the internet to analyze its competitors’ prices. Amazon then tinkers with its prices to charge the most it can for every transaction.

The problem is that Amazon might use its position and knowledge unfairly, especially in the way it competes with the third-party sellers vying for business on its own site. After all, Amazon can and does actively work to gain a price advantage over all its competitors.

Amazon wants its sellers and suppliers to offer a price-plus-shipping that is “Prime eligible.” That means the item is either sold by Amazon or sold by a third-party “FBA,” or “fulfilled by Amazon,” and either way ships from Amazon’s warehouses.

Consequently, Amazon assures that “the Prime-eligible offer always wins the best position in its search results, and that could be up to 10 percent more expensive and still be presented to you as the lowest price—but still not actually be the lowest price,” says James Thomson, former business head of Amazon Services, and now a partner in Buy Box Experts, consultants for third-party Amazon sellers.

Investment advisors marvel at how Amazon’s price advantage prompts customers to buy more and “convert” just-looking-around users into purchases.

But regulators are beginning to wonder if Amazon’s practices might threaten consumers. In July, the E.C. launched an investigation to determine whether Amazon’s conflicting roles as a mega-retailer and a marketplace for competing third-party retailers gives it an anticompetitive advantage. According to the commission’s preliminary fact-finding, Amazon appears to use the data it collects from its competitors, their products, and their transactions.

“E-commerce has boosted retail competition and brought more choice and better prices. We need to ensure that large online platforms don’t eliminate these benefits through anti-competitive behavior,” says Margrethe Vestager, the E.C.’s commissioner in charge of competition policy, in a press release.

Amazon is now reportedly also being investigated by the FTC.

How to Find the Best Prices Anyway

Despite efforts by manufacturers, retailers, and internet overlords to reduce price competition, you can often still find deals.

We tasked one of our undercover shoppers to shop ’til she dropped for 30 big-ticket items (electronics, large and small appliances) using 44 different retailers, search engines, online aggregators, and other strategies. Her mission? Find which ones were winners and which were duds. Below, we describe the rules we followed.

When we compared major retailers’ overall prices across all 30 items on our shopping list, none of the largest retailers or search sites stood out. For the items they sell, there were no remarkable price standouts among Amazon, Best Buy, Google, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Target, and Walmart.

Nevertheless, our shopper found it was sometimes still worth her time to take a few extra minutes to check prices at these mega-sellers. For example, Amazon had the second-lowest price, $249, for a 9.7-inch 32GB iPad Wi-Fi in silver, vs. $277 at Google’s lowest-priced retailer and $330 at Best Buy and Target.

But often we had to cast a much wider net to find better-than-usual deals. For example, for four of our 30 items, price differences among the biggest retailers were only $1 or $2, but seeking out offers from smaller players found us far better pricing.

Here are shopping strategies that might be worth your time:

Call or Email Local Retailers

In our tests, this was hands-down the best way to find a deal, especially for major appliances and computers.

MAP policies prevent retailers from advertising lower-than-allowed prices, but they don’t constrain retailers from selling products for less. Our undercover shoppers find that by calling or emailing stores for quotes, they are often offered prices lower than advertised—especially when contacting independent stores.

The trick is to let salespeople know you’re contacting multiple stores and asking each for its best possible price.

The trick is to let salespeople know you’re contacting multiple stores and asking each for its best possible price.

Don’t be shy or think this approach involves difficult negotiations. Just be polite and businesslike. We find salespeople are accustomed to providing discounted pricing when asked. It’s what contractors often do to find the best deals.

Calling and emailing retailers yielded the lowest prices our undercover shopper could find anywhere for 15 of the 30 big-ticket items on her list, making our method of collecting competing offers by far the most consistent strategy for finding bargains.

But don’t conclude that contacting just one local store means you’ll get the best prices. Many local stores offered high prices, too. You have to collect multiple prices from several to find the gems—usually contacting four or five retailers is enough.

Google and Bing

As explained earlier, Google doesn’t always provide the lowest prices for products, even if that’s what you asked it to do. Often it steers users to businesses that pay it commissions or for advertising, not to those offering the best deals.

Nonetheless, our shopper still found it worth her while to include Google and Bing in her hunt. For eight items, one or the other identified the best bargains she could find (although often these search engines steered her toward one of the mega-retailers she was already checking).

Warehouse Clubs

When we compared prices for more than 200 items at Amazon, Costco, Target, Walmart, and other big retailers, we found Costco usually offers good prices for the products it carries. For its somewhat limited selection of big-ticket items, Costco’s prices overall were about four percent lower than the average prices at other retailers. But those savings don’t factor in Costco’s $60 a year basic membership fee.

You’ll have to do a bit of math to decide whether the savings and benefits you might get from a warehouse club (or by paying $119 a year for Amazon Prime) warrant its annual fee.

CamelCamelCamel.com

A major disadvantage for bargain hunters is that prices change all the time, and there’s no way to predict when the best deals will show up.

CamelCamelCamel.com constantly tracks prices on Amazon and its third-party seller marketplace. It lets you search for the make and model number of a product you’re interested in, and then displays its day-by-day price history—if it follows it (Camel doesn’t track everything Amazon sells).

CamelCamelCamel.com constantly tracks prices on Amazon and its third-party seller marketplace. It lets you search for the make and model number of a product you’re interested in, and then displays its day-by-day price history—if it follows it (Camel doesn’t track everything Amazon sells).

For example, using Camel we learned that when a 55-inch Sony TV on our shopping list first hit the market in August 2018, Amazon was selling it for $798. A year later its price had dropped to $748. However, for a couple of weeks last March, Camel reported that Amazon cut the price to $580, before it bounced back to $748.

By knowing how low a price can go, shoppers can set a target to shoot for. But, of course, there’s no way to predict whether a price will dip back to its minimum. So Camel (and several other websites) let you set price alerts for products, and email you if the price drops below a threshold you set—say, $600 for our Sony TV.

We set up Camel low-price alerts for the products we price-shopped at Amazon. Camel alerted us to price drops for four of our items. Two of these let us know about savings ranging from just $10 to $30. But the other two alerts saved us a lot more, from chopping off $80 for a Dyson hair dryer to scoring us $106 for a specific LG TV model.

However, if we had bought our items at the prices reported by Camel as historic lows, we would have bought at the lowest prices we could find for 15 of them.

Keep in mind that historic prices vs. current prices really aren’t directly comparable. And we can’t really confirm that the lowest prices reported by Camel were actually paid by shoppers—we have to take the site’s word for it that our TV and other stuff was actually listed for the lows it reports. But we think Camel is worth consulting and, if you have time, it’s worth setting up price alerts for items you’re thinking about buying.

See If the Price Goes Down When You Add an Item to Your Online Shopping Cart

Many MAP rules don’t consider it advertising when retailers show lower prices after customers place items into online shopping carts or otherwise click links to see what prices they’ll get. This type of action is thought of as part of the sales transaction, not advertising, so retailers sometimes slyly skirt MAP rules and tip off shoppers by asking them to “See price in cart” or to “Click to see buying details.” If you encounter either option, try it—it’s a super-easy way to maybe get a bargain.

Unfortunately, our testing didn’t find a lowest price using this method for the 30 items we compared. But sometimes adding an item to our cart led to a free printer along with a laptop purchase or gratis software and TV mounting.

GoSale and PriceGrabber

GoSale and PriceGrabber

Several shopping sites promise to uncover the best deals by crawling the internet to scrape billions of prices. We tried out four—GoSale, Kelkoo, PriceCheckHQ, and PriceGrabber. We found GoSale and PriceGrabber were worth our shopper’s time. GoSale identified the lowest prices we could find for six of the items on our shopper’s list.

Like Camel, GoSale also has price histories and a price-drop alert service (which we did not test).

Although we include GoSale and PriceGrabber in our worth-a-shot list, a drawback to using them and other price-searching sites is that they often steered our shopper toward false lowball leads. Many of the low prices she found weren’t available when she tried to buy the items, or led to sellers that hadn’t disclosed their deal applied only to a refurbished, used, or open-box item, or to a different, less expensive model than what she sought.

eBay

MAP is not an impenetrable fortress. Many retailers commonly advertise prices below the minimums set by manufacturers. “Violators do exist,” says Ayelet Israeli, assistant professor of business administration at the Harvard Business School.

The best place to find these bad boys probably is eBay. In a 2016 study, Israeli and two other researchers tracked MAP violations by 959 online retailers selling 226 new (not used or refurbished) electronic and music products produced by one manufacturer by working with a MAP monitoring service, which crawled the internet at least daily to find violators.

Overall, 31 percent of almost 1.3 million daily price observations over a one-year period were below MAP. And the discounts were pretty good: About 17 percent of violators offered price discounts of 10 percent or more below MAP.

On eBay, however, 28 percent of violators offered price discounts of 10 percent or more below MAP.

In our testing, the best prices we found on eBay were about six percent lower than average. For three of our items, an eBay seller offered the lowest price our shopper could find. So we think it’s worth checking eBay if you’re having trouble finding low prices elsewhere. But Israeli cautions these sellers might not offer free shipping or a wide assortment of goods.

See If Comparable Products Cost Less

No matter what you buy, shopping around for the best price will often save you money. But you’ll save even more by considering comparable-but-less-expensive products. For example, when shopping for a TV, consider buying a typically lower-priced Toshiba instead of a Samsung.

Consult Consumer Reports’ ratings to find high-quality products. Often it recommends models that are less expensive than lower-scoring competing products.

Also compare prices of store-brand versions. For example, Costco’s private-label Kirkland products tend to get high marks for quality.

And consider buying used or refurbished items. Our shoppers found big savings on used and refurbished electronics. If you go this route, buy only from manufacturers that offer strong warranties and no-questions-asked return policies.

Save Even More by Using Our Other Shopping Tips

Click here for additional strategies and our top tips for saving when buying online, regardless of what you buy. Often, after you’ve identified the best price for something, additional simple steps—signing up for email lists, using coupon codes, buying through a cashback portal—can cut your costs by even more.

Rules of the Chase: How We Shopped for the Best Prices

- Our researcher shopped 44 ways for the best price for each of 30 big-ticket products—computers, major home appliances, smaller appliances and electronics, and TVs. She sought deals at major retailers, including Abt, Amazon, Best Buy, B&H, Costco, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Target, Sears, and Walmart. She searched using Google, Bing, and Yahoo. She tried out various price-comparison and tracking sites. And she called local stores to collect competing bids.

- For online stores, we added in shipping costs, where applicable.

- We did not accept prices for used, refurbished, and open-box merchandise. We also rejected prices from third-party sellers at Amazon, Sears, and Walmart if they had fewer than 100 reviews and customer satisfaction ratings of less than 4 or 5 stars.

- For price-comparison websites, we clicked through to the product to make sure we could buy it for the same price that the shopping bots claimed it was.

- For Costco, we did not try to adjust its prices to account for its annual membership fee, nor did we include Amazon’s annual fee to get free shipping or special offers from its Prime option.